Path Photographs

Figure 1: © Rashed Haq, Untitled (2023)

On a forest-bath trip last summer, I found myself remembering path photographs that have stayed on my mind over the years, as I walked through the woods (figure 1). From the time when photography was invented, photographs of paths and roads have been popular for their ability to pull the viewer into the image, evoke emotions, tell stories, and capture the essence of moving through the world. Winding through natural and human-made landscapes, paths are the storytellers of forgotten tales, echoing the footsteps of those who came before us, and providing the courage to forge ahead.

It is difficult to narrow down from the (literally!) hundreds of memorable path photographs down to a handful—but some of my favorites are below.

Figure 2: Roger Fenton, "The Valley of the Shadow of Death" (1855)

Path photographs can capture something beyond beauty. Roger Fenton's (1819-1869) "The Valley of the Shadow of Death" (figure 2), shows the toll of war on the landscape. Fenton was a British photographer considered one of the pioneers of documentary photography. Taken during the Crimean War, Fenton's composition draws the viewer's attention to the road's meandering path, leading the eye through the landscape, seemingly peaceful at first glance. However, on closer examination, the viewer is confronted with the presence of discarded cannonballs scattered along the path. The contrast between the untouched landscape on either side of the road and the chaotic destruction implied by the cannonballs in its center speaks to the devastating consequences of war on both the physical environment and human lives. Interestingly Fenton decided to carefully rearrange the cannonballs on the road, rather than capturing them as they naturally lay where he found them. This has raised questions about the relationship between truth, manipulation, and the photographic medium itself.

Figure 3: Eugène Atget, "Rue Saint-Rustique" (1922)

Eugène Atget (1857-1927) was a French photographer known for his documentary images of Paris. Using a view camera on a tripod and glass plate negatives, Atget made more than 8,500 photographs of Paris, capturing the disappearing aspects of the city's architectural heritage. His photographs often focused on narrow alleys, courtyards, and neglected corners of the city, showcasing the beauty and character of these overlooked spaces. Atget’s photograph "Rue Saint-Rustique" (figure 3) portrays a narrow cobblestone road, flanked by walls of buildings, drawing the viewer's attention and guiding the gaze deeper into the image. His meticulously chosen angle and framing highlight the lines, textures, and architectural elements, emphasizing the sense of depth. Atget's photographs encapsulates his iconic approach to capturing the Paris of his time, evoking a sense of history and nostalgia, and preserving the essence of a rapidly changing urban landscape.

Figure 4: © Todd Webb, "Desert Highway, Humbolt Valley, Nevada” (1955)

Todd Webb (1905-2000) was an American photographer known for his insightful documentary photographs that captured the essence of everyday life and urban landscapes, particularly New York and Paris. Webb was influenced by the photos of Atget that he saw in the New York apartment of his friend and fellow photographer Berenice Abbott, who had acquired Atget’s works and brought them back from Paris. In the mid-1950s, Webb embarked on a cross-country journey by boat, bicycle, and foot, capturing the diverse landscapes and communities of America. His photograph from this coast-to-coast journey titled "Desert Highway, Humbolt Valley, Nevada” (figure 4), captures the essence of a road journey. It features a seemingly endless stretch of desert highway, cutting through the vast, barren landscape of Humbolt Valley. The open road takes center stage as a metaphor for exploration, escape, and the pursuit of the unknown.

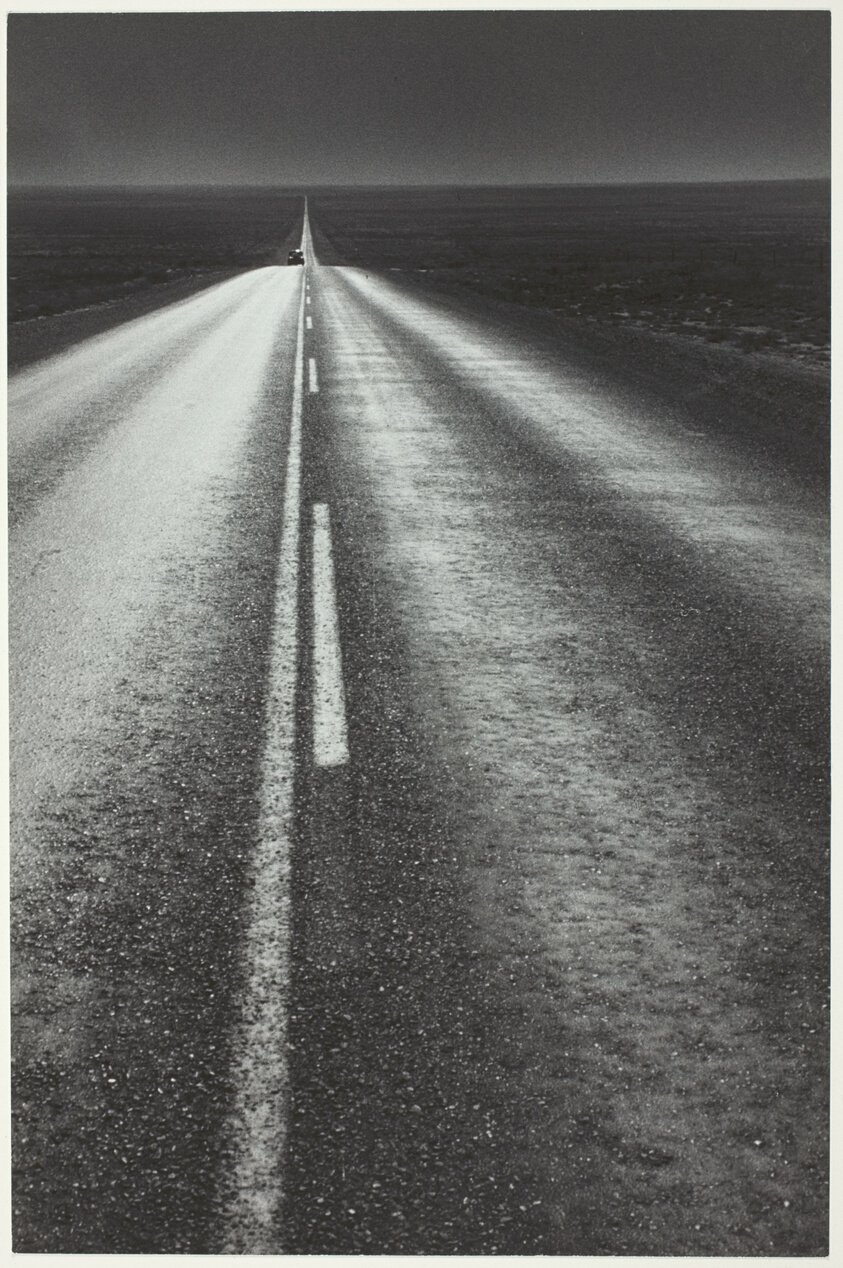

Figure 5: © Robert Frank, "US 285, New Mexico” (1956)

Robert Frank (1924-2019), who needs no introduction, took a road trip across the US at the same time as Todd Webb. Frank’s photograph from this trip titled "US 285, New Mexico” (figure 5) features a long, straight road stretching towards the horizon, cutting through the expansive New Mexico desert. The road becomes the central element of the composition, occupying ~70% of the surface of the photograph, dominating the composition, and inviting viewers to project themselves onto the road, imagining their journey through the American Southwest. The monochromatic tones and stark contrast add depth and visual impact to the image, rendering the texture of the road. The subtle nuances of light and shadow of where the tires of cars fall vs. not, add a layer of gritty richness to the image. The absence of any visible human presence creates a sense of introspection and the idea of a personal journey. While Frank and Webb were not aware of each other’s cross-country work yet, they would have been aware of Dorothea Lange’s “The Road West, New Mexico” (1938). (As an aside, don’t miss the MFAH exhibition by the amazing Lisa Volpe, “Robert Frank and Todd Webb: Across America, 1955,” and the associated catalog.)

Figure 6: © Ishiuchi Miyako, “Yokosuka Story #98” (1977)

Ishiuchi Miyako's (b1947) series “Yokosuka Story” (1976-1977) depicts the town of Yokosuka, Japan, where Ishiuchi grew up during the years of military occupation when the town was the site of a large American naval base. The series explores the tension between local and foreign influences, past and present, and the uncertain future of Japan's identity. Ishiuchi, associated with the 'Provoke' movement, documents the town's visual landscape and the struggles of being Japanese in a rapidly changing post-war society, offering a subjective and radical vision of urban life. I cannot decide if “Yokosuka Story #98” (figure 6) feels like a dream or a nightmare. It is a paradoxical sight where day and night unite, where the nocturnal darkness seems to be illuminated by the harsh mid-afternoon sun. In the image, a smiling child skips alone down a street, unfazed by “the shadows cast by surrounding buildings threatening to overtake her. The dark tones of the girl’s coat and hair, along with her shadow, make her look like a ghostly apparition, perhaps a stand-in for Miyako’s childhood self” (Abe Ahn).

Figure 7: © Thomas Struth, “Crosby Street, New York” (1978)

Thomas Struth (b1954), a German contemporary photographer who studied under Hilla and Bernd Becher at the Düsseldorf Academy in the late 1970’s, is known for his large-scale, meticulously composed images that explore themes of architecture, landscapes, and human presence within urban and natural environments. “Crosby Street, New York” (figure 7) from the series “Unconscious Places,” presents a gritty urban street scene with litter and debris scattered across the unkempt road. The buildings flank the street with their repetitive patterns of windows and fire escapes, creating a rhythmic architectural formality that contrasts with the disorder of the street. The image is characterized by a sense of abandonment and neglect, because of the debris and the absence of people, further enhanced by the deep shadows of the doors and windows. The empty streets, familiar more recently from the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, evokes feelings of the transience of human endeavors in the face of time and nature.

Figure 8: © Flor Garduño, “Camino al Camposanto / Road to the Cemetery, Ecuador” (1988)

Flor Garduño (b1957), a Mexican photographer, is known for her poetic black and white images showing the rich tapestry of indigenous communities and contemporary Latin American photography. Her photographs are characterized by their intimate and lyrical quality, often infused with elements of magical realism. Garduño's works provide a window into the intricate relationship between humans and the natural world, the blending of myth and reality, and the resilience of diverse indigenous cultures of Latin America. "Road to the Cemetery, Ecuador" (figure 8) is a poignant and haunting image that captures the essence of mortality and the spiritual connection between life and death. The photograph depicts four lone figures carrying a child’s coffin on a journey not of their choosing. They walk down a road that disappears into the misty atmosphere, reflecting a transmigration from the realm of the living to the realm of the spirits. The arrows on their path point in the direction opposite from their journey, as if they are walking in a forbidden direction. Garduño bears witness to the fragility of life, and the resilience of the human spirit to find strength even in the face of the unimaginable.

Figure 9: © Sebastião Salgado, “Untitled (from the series Kuwait)” (1991)

Sebastião Salgado (b1944), the acclaimed Brazilian photographer, is known for his socially conscious work. His photographs from the Kuwait series, shot in 1991 as the Gulf War drew to a close, capture human resilience amidst devastation. The series depicts oil wells set ablaze by Saddam Hussein’s retreating forces, engulfing the surroundings in thick smoke and flames. In one of these photographs (figure 9), Salgado captures a shepherd with his sheep on the road. In stark contrast to the devastation and chaos surrounding him, the shepherd and his flock become symbols of resilience, an element of relative tranquility. You can feel a sense of quiet determination and perseverance in the shepherd's posture and the way he gazes into the camera. Salgado's photographs from the Kuwait series serve as a reminder of the environmental devastation caused by conflict and the destructive effects of oil extraction.

Figure 10: © Munem Wasif, “Untitled (from the series Salt Water Tears)” (2009)

Bangladeshi photographer Munem Wasif’s (b1983) photographs from Satkhira, a region in southwestern Bangladesh, focus on the impact of saltwater intrusion, and an example of his thought-provoking and socially engaged work. Satkhira is known for its vulnerability to climate change and rising sea levels, resulting in the contamination of freshwater sources with saltwater. Wasif's photographs capture the enormous consequences of this ecological challenge on the lives and livelihoods of the local communities. Figure 10 shows three brothers pushing their boats through low tide into the sea following an ephemeral path, with the boats filled with fresh water which they have collected inland and need as their daily drinking water. It takes the brothers three hours each way to make the journey. This challenging path that the brothers have to endure, like millions of other families, also acts as a metaphor for the current challenge of climate change that we are collectively grappling with.

Figure 11: © Matt Black “Country Road. Lindsay, California” (2013)

In his series “American Geography,” Matt Black (b1970) traveled 100,000 miles cross-country five times, on buses and driving a van, criss-crossing through 46 states, guided by what he calls “concentrated poverty” — cities, towns, and counties with poverty rates above 20%. He said he wanted to “Just go see. Go see from this kind of ground level perspective what the country actually looks like.” What he discovered was a contiguous geography of poverty. Through his photographs, Black, who is an American Magnum photographer, delves into the often-overlooked corners of American society, examining the impact of poverty, inequality, and systemic issues on communities. His images not only evoke empathy but raise questions about the larger societal forces at play. By documenting the realities of these American geographies, Black provides a visual narrative that challenges common perceptions and exposes the disparities that exist within the nation. Figure 11 depicts a sinewy country road that Black came across during his travels, symbolizing the stops and turns these communities face.

Figure 12: © Todd Hido, "#11385-1781” (2014)

Todd Hido (b1968) is an American contemporary photographer known for his atmospheric images of suburban and domestic landscapes. Hido's photograph "#11385-1781” (2014) (figure 12) showcases his distinctive style and ability to evoke a sense of mystery and narrative. The photograph features the stillness of a snowy night with a dimly lit road in what looks like a rural area. This image draws the viewer into the space, as if we can feel our lungs filling with the crisp night air making us want to wrap the scarf tighter around our necks. The twirl and whirl of the falling snow illuminated by beaming light contrasts with the stillness and quietude of the surrounding environment. The image feels like a fragment of memory, soaked with longing and melancholy, leaving us to wonder about the stories that may be hidden within the scene.

Figure 13: © Jungjin Lee, “Opening #24 (from the series Opening)” (2015)

Jungjin Lee's (b. 1961) photography delves into the exploration of landscapes and the intersection of nature and human experience, often evoking a sense of monumentality and transcendence. Lee’s photographs lack human presence, instead emphasizing the earth and sky as charged spaces filled with tangible energy and possibility. Lee employs a unique process involving Korean Hanji paper and a combination of analog and digital techniques. The lush prints display a distinctive textural quality, akin to a blurry video footage, adding depth and a feeling of looking through layers of time. Lee's images prompt viewers to assign anthropomorphic qualities to the landscapes, evoking limbs, joints, and orifices, creating a sense of connection and intrigue. “Opening #24” (figure 13), depicts a narrow path squeezing its way through two tall rocks that stand like guardians, and winding deeper into the heart of the image. The uncommon vertical aspect ratio accentuates the height and majesty of the rocks, making them appear like ancient sentinels that have earned wisdom over epochs by partaking in an age-old conversation with the sky. Like her other images, it invites contemplation, reflection, and appreciation for the wonders of nature and our relationship with it.

Figure 14: © Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad, "Night Journey of Forest Dwellers (from the series Fields of Sight)” (2016)

In her series "Fields of Sight" (2014-2016), photographer Gauri Gill (b1970) ventures to the verdant landscapes of the west coast of India, particularly in the predominantly adivasi district of Dahanu, Maharashtra, collaborating with Warli artist Rajesh Vangad. Gill's photography often delves into socio-cultural and political themes, focusing on marginalized communities and their stories. She combines elements of documentary and fine art photography to create compelling visual narratives that challenge societal norms and shed light on the lived experiences of individuals and communities. Through their collaboration, Gill and Vangad navigate cultural, social, and artistic differences, bridging gaps of class, education, and location. The series captures Vangad's role as a guide, a subject in the photographs, and an artist who paints over the images, adding his own symbols and iconography — a fusion of photography and painting, blurring the boundaries between the two mediums. The series only showcases the artistic collaboration between Gill and Vangad but also touches on broader themes such as the representation of indigenous communities, the intersection of traditional and contemporary artistic practices, including the exploration of mythic and ritualistic symbols within the context of the changing landscape. The series delves into the complexities of cultural exchange, power dynamics, and the transformative possibilities of collaboration. The result of their collaboration is a feast for the eyes where “Night Journey of Forest Dwellers” (figure 14), set in the heart of an enchanted forest with a kaleidoscope of leaves and birds, is a magical example full of whimsy and charm.

Figure 15: © Keith Carter, “Starry Night (from the series Ghostlight)” (2021)

Keith Carter (b1948), an American photographer and a recipient of the Texas Medal of Arts, is celebrated for his evocative and poetic images that transcend the boundaries of traditional photography. Carter's work explores themes of memory, mythology, and the human connection to nature. His photographs often possess a dreamlike quality, characterized by rich textures, soft focus, and a distinct sense of narrative. Carter’s mastery of capturing the ephemeral and the mystical is evident in his photograph “Starry Night” (figure 15) where he combines the everyday, represented by the car driving down the road with its piercing headlights, with the celestial symphony unfolding in the sky. It reminds me of my night drive up Route 1 in California on a moonless night, where the stars wrapped the sky from horizon to horizon.

Figure 16: © Paul Seawright, “Valley (from Hidden series)” (2002)

A good place to conclude is with Paul Seawright's photograph titled “Valley” (figure 16). Seawright was commissioned to undertake a series of images of the war in Afghanistan by the Imperial War Museum in the UK. This series is a striking exploration of the aftermath of conflict and the lasting impact it has on landscapes. Seawright is said to have said “I’ve made a Fenton!” about this image. The juxtaposition here of beauty and danger creates a sense of unease, prompting viewers to question the hidden stories and the potential dangers that lie beneath seemingly tranquil surroundings. Seawright's photograph becomes a visual metaphor for the haunting remnants of conflict, emphasizing the enduring scars and the lingering threats that persist long after the battles have ceased.

These path images remind us that as long as paths exist and photography exists, artists will continue to draw us in with their path images and captivate viewers.